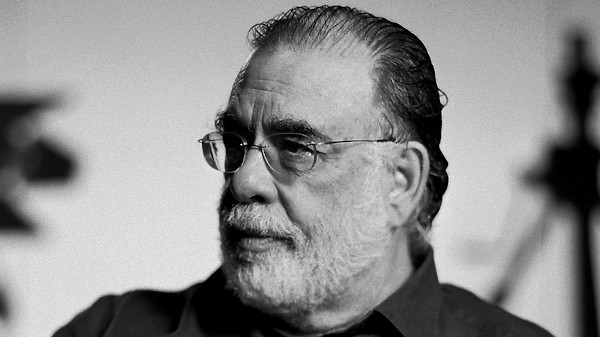

A Conversation With Francis Ford Coppola

As Part Of The Festivities Of The TCM Classic Film Festival 2016, The Legendary Director Sat Down With Ben Mankiewicz To Discuss The Conversation And His Most Famous Project

By Tom Johnson

Published on May 2, 2016

The cement was barely dry from the hand- and footprint ceremony in the forecourt of the TCL Chinese Theater (Grauman’s Chinese) in Hollywood where director Francis Ford Coppola had just been enshrined before he took the stage to talk about some of his seminal 1970s films with TCM Classic Film Festival host Ben Mankiewicz.

Ostensibly, Coppola was there to talk about his 1974 psychological thriller, The Conversation starring Gene Hackman and John Cazale, a brilliant, personal film sandwiched between the monolithic twin towers of The Godfather and The Godfather: Part II.

But, even though The Conversation was the movie to be screened Friday afternoon for an overflow audience, placing a moratorium on Godfather questions was like ignoring the 500 lb. gorilla in the room – impossible for Mankiewicz to do.

For his part, Coppola made the transition into a Godfather discussion easy. Mankiewicz mentioned that the director had, inexplicably, been sweeping up backstage prior to coming out.

“Always at these beautiful events, you come out and bask in the presence of the public but in the back it always looks to me like a place where an assassination is going to happen,” Coppola said. “At least I try to sweep up so the post-mortem pictures will look good.”

Far from a sure thing in the early 1970s, organized crime movies hadn’t always done well commercially. Coppola cited one called The Brotherhood that had bombed at the box office and cast a pall over other directors taking a shot at the genre.

“Directing The Godfather wasn’t considered a great career move,” Coppola said. “A lot of directors turned it down. I know Costa-Gavras and Peter Bogdanovich turned it down as well as the great Elia Kazan. I had made a film called The Rain People that I had written, and it was promising. I wanted to make personal films that I also scripted from scratch – story as well as screenplay.”

According to Coppola, Robert Evans who ran Paramount Studios at the time felt he was hedging his bet by hiring the fledgling director.

“I was making my living as a screenwriter so they felt that if the script needed some work, I would be able to pitch in and do it without charging a separate fee,” Coppola said. “Secondly, I was young and unproven which might mean that I might have some knowledge of the new equipment beginning to find its way in the film business, but more importantly, I could be pushed around. And thirdly I was Italian American. Those are the reasons I was given the job.”

Coppola remembered the first Godfather film as an unmitigated nightmare. At the time, he had two sons and his wife was pregnant with a third child. “I had absolutely no money,” he said. “They weren’t happy with what I was doing, my decisions and choices either in the way I wanted to make the film or the actors I wanted. I really was waiting to get fired each week. It was such an unpleasant experience to be unwanted by the management for so long that there was no possibility that I would want to do a second film. I wasn’t interested in gangsters.”

Paramount management’s lack of confidence in Coppola during the shooting of The Godfather extended to casting. “They didn’t like Al (Pacino); they didn’t like or even want Marlon (Brando). It sounds funny but you always have to look at these things in the context of the period. Marlon had been in a film called Queimada, which was not successful and he was supposedly very difficult and would cause the production lots of delays which didn’t turn out to be the case.”

Coppola had no intention of directing the Godfather sequel in 1974 and even suggested they hire an up and coming director named Martin Scorsese to direct. Paramount nixed that idea. Coppola finally came around when the studio acquiesced to three conditions: that he be given total creative control, that he be paid $1 million in salary (a fantasy amount back then) and that the name of the movie have “Part II” in the title.

“This was the sticking point,” Coppola said. “They didn’t want to have a movie called ‘Part II.’ They felt it would be confusing to the public, that they’d think it was the second half of the movie they had just seen. There had never been an American movie called, something, Part II.”

Coppola got his way and went on to helm what is considered to be the greatest sequel in movie history (many film buffs actually prefer “Part II” to The Godfather).

As the conversation turned back to The Conversation, Coppola remarked that he had originally approached Brando for the role of surveillance expert Harry Caul, the part that Hackman eventually played.

“A year and a half before The Godfather, I had the script of The Conversation and I was trying to get someone to let me make it,” he said. “You literally have to go hat in hand and beg and no one was interested. I actually spoke to Marlon on the phone which was a thrill for a New York theater school guy like me at that time. He told me he admired it but he didn’t think it was for him and he turned me down.”

The germination that became The Conversation began when Coppola saw the classic 1966 Michelangelo Antonioni film, Blow-Up.

“I thought it was a beautiful film, the kind of movie I wanted to make; it was personal, mysterious, had narrative drive. In those days, younger filmmakers in our 20s wanted to make personal films. We had been imprinted by all the films that had come from Europe.”

During shooting of the film, Coppola remembered the daily struggle Hackman had with staying in character as Harry Caul, an unhappy, lonely, unattractive man that has trouble maintaining relationships or any kind of meaningful human connection.

“It used to bug Gene to have to get into that character’s persona,” Coppola said. “He became very grumpy. And then at the end of the day, he’d be cool and he’d be this bon vivant guy in San Francisco. But he was very uncomfortable in that role. I always suspected it was because the character was similar to what Gene had inside himself deep down. I never got to really know that but he was not pleasant or happy in that role, although he later told me that it was his favorite performance that he had ever given which was thrilling for me to learn.”

Apart from the classic opening telephoto shot from a rooftop on Union Square in San Francisco that follows a street mime (Robert Shields of soon-to-be Shields and Yarnell fame) and Walter Murch’s stunning sound design, what quickly strikes many viewers is the see-through raincoat that Hackman wears in the opening scene and then throughout most of the movie.

“I always in my mind have what the theme of the movie is boiled down to a word or two,” Coppola said. “In the case of The Conversation, the theme was privacy. So when the costumers asked me what kind of coat Harry should wear, I wasn’t sure and looked at some Humphrey Bogart-type trench coats. One was a plastic raincoat that was transparent. I thought if this film is about privacy, it’s interesting to have a transparent raincoat. And that’s how that choice got made.”

If The Conversation was about privacy and The Godfather about succession, Coppola said the theme of Apocalypse Now was about “what happens when you put 15 million volts into a 110 electrical circuit and see what blows out.”

“No one wanted to back Apocalypse, so I borrowed the money to make it,” he said. “In those days – during the Carter years – interest was 29 percent. There I was, this kid from Queens and I owed $32 million. When the film came out critic Frank Rich said that it was the biggest disaster in the movie industry in the last 50 years. I kept thinking: ‘Gee, isn’t there anything worse?’

“I don’t know in the interim if he’s changed his mind or if he even should,” Coppola continued. “The truth of the matter is that when you’re working in the arts, you’re taking chances and experimenting with what you think something should be and if you have the right instincts, sometimes you’re right and over the years, people begin to see it that way. When Apocalypse came out it was totally creamed by Kramer vs. Kramer. We were very discouraged. But I noticed that people over the years would still go see my movie.”

Tom Johnson has been an entertainment journalist for more than 30 years and co-authored the 2004 book, Reel to Real: 25 Years Of Celebrity Profiles From Vaudeville To Movies To TV with David Fantle. He is also a former senior editor for Netflix.

Most Popular

About Us

Login

Contact Us

Subscribe

Advertise With Us

Copyright 2010 to 2020 Modern Times Magazine and Modern Communications. All Rights Reserved.

Terms of Service

Privacy Policy

Login

About Us

Contact Us

Subscribe

Advertise With Us

Copyright 2010 to 2020 Modern Times Magazine and Modern Communications. All Rights Reserved.